Thalassemia, a genetic disorder caused due to defect in the gene coding for globin chains of haemoglobin, affects more than 400,000 new-borns every year worldwide. Thalassemia major children do not show signs or symptoms in their infancy and cannot be diagnosed clinically or with routine diagnostic tests.

Depending on the genes involved the disorder can be categorised into alpha thalassemia, beta or delta thalassemia. Of these, beta thalassemia is the most severe form also known as “Cooley’s anemia” which requires lifelong blood transfusions.

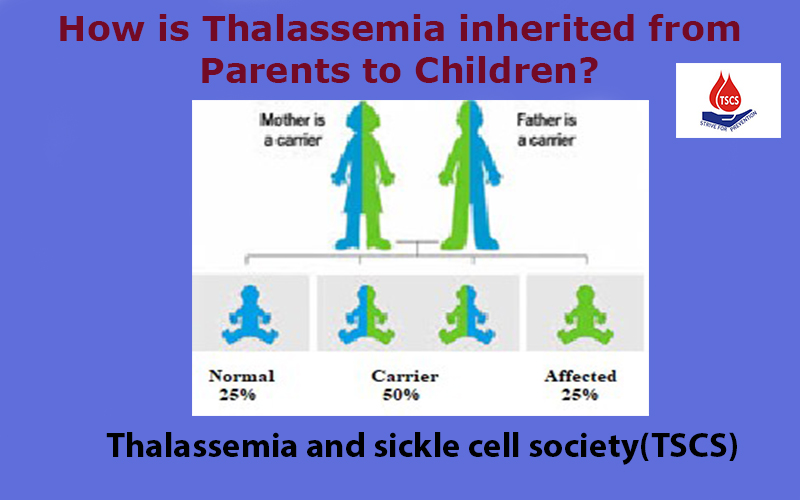

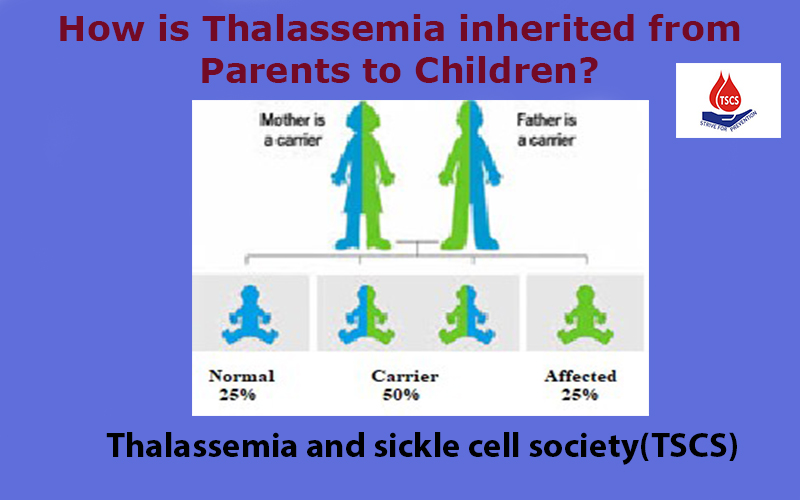

How is thalassemia inherited?

It is passed on from the parents to children through genes one from each parent (genes occur in pairs with one gene inherited from father and other from mother). It is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner i.e. two defective alleles (genes) are required for the disease condition to be expressed. An individual carrying only one defective gene is said to be carrier/trait/minor and an individual with two defective genes is called thalassemia major.

If both the parents are carriers then there is a 25% chance that the child may be normal, 50% that the child will be a carrier and 25% chance that the child may be patient or thalassemia major. Thalassemia carriers are asymptomatic with mild or no anemia. However, their haemoglobin levels may reduce under stress due to puberty, pregnancy or infection and may require treatment. They may have iron deficiency and may require treatment with iron supplements.

Signs and symptoms

Thalassemia major children do not show signs or symptoms in their infancy and cannot be diagnosed clinically or with routine diagnostic tests. Around 90-95% thalassemia majors start showing symptoms within 3-24 months. They present with persistent and progressive pallor (pale appearance), poor appetite, weakness, lethargy and delayed milestones. On examination they will have anemia of moderate to severe degree along with enlarged liver and spleen. Children diagnosed at later age have typical thalassemia facial features (frontal bossing, prominence of of facial bones, forward protrusion of upper teeth, and depression of nasal bridge). Inadequately transfused thalassemia major also show similar symptoms.

How to diagnose a thalassemia major child?

If there is any suspicion of thalassemia in a child, then the following investigations have to be done to confirm the diagnosis:

Complete Blood Count (CBC): CBC using an automated cell counter will reveal haemoglobin (Hb) level <7 gms/dl, WBC counts mildly elevated, MCH (Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin) and MCV (Mean CorpuscularVolume) reduced and MCHC (Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration) will be normal.

Peripheral blood shows microcytic hypochromic picture along with anisocytosis, poikilocytosis, broken red cells and target cells. Large number of nucleated RBC’s will be seen.

High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Hemoglobins are of three types depending on the stage at which they are expressed – HbA, HbA2 and HbF. In thalassemia major, Hb electrophoresis or Hb HPLC will reveal HbF 70-99%.

Biochemical Tests: Unconjugated bilirubin may be high. Serum iron, transferrin saturation and serum ferritin may be normal in early infants but are elevated if the diagnosis is delayed.

DNA Testing: DNA analysis detects the type of mutation/defect in the beta globin gene causing thalassemia major. More than 250 changes have been reported to be causing the disease.

All these tests should be done before putting them on transfusion to rule out whether it is thalassemia or other causes including iron deficiency anemia.

An Early Diagnosis can reduce the mortality among the children affected with this disorder.

Dr. Padma G

Research Scientist, TSCS

Co-authored

Dr. Suman Jain

Chief Medical Research officer and Secretary

TSCS- Thalassemia and sickle cell society, Hyderabad